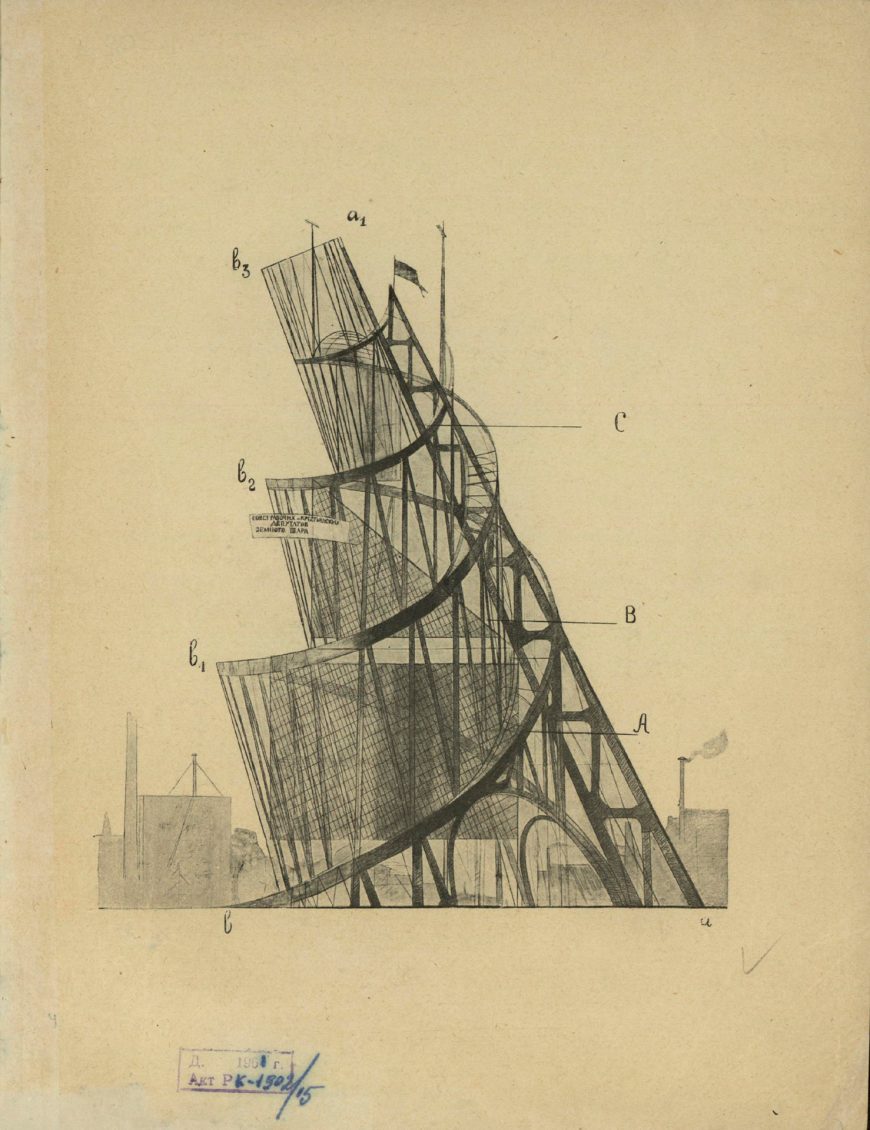

On the cover of my new book Vladimir Tatlin and his colleagues are building a model of his Monument to the Third International for the third anniversary, in November 1920, of the Bolshevik Revolution. As conceived by Tatlin, the tower was to be 400 metres tall: taller than the Empire State Building (381 metres, 1931) and dwarfing the Eiffel Tower (300 metres, 1889). Construction was never started because of the enormous amount of steel required; whether it could then even have been built is an open question. It remained a utopian project. As a finished object it was only ever a model, or a drawing:

Pamyatnik III internatsionala. Proyekt khud. E. Tatlina [Памятник III интернационала. Проект худ. Е. Татлина]. Department of Visual Arts of Narkompros, St. Petersburg, 1920

That Tatlin and his colleagues are so absorbed in their work of modelling the future alludes to the theme of the book, tracing the formation and early development of the vision of economics as a modern science, validated by this status. But this visual connection to the theme of the book also has a direct link with the title. For Tatlin was the leading representative of “Constructivism”, a Russian art movement that was the subject of an important exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery from February to April 1971. And more generically of course, social constructionism has been the core of many of the intellectual trends and fashions from the later 1960s to the present. But while the book owes a great deal to Tatlin and his comrades, it owes little to the various post-modernist trends that have come and gone since the 1970s.

In April 1971 I visited the Hayward Gallery exhibition, having a particular interest in early Soviet film-making. The exhibition catalogue (Art in Revolution. Soviet Art and Design since 1917, Arts Council, London n. d.) was introduced by Camilla Gray-Prokofieva, whose 1962 study of modernist Russian art had just been republished as The Russian Experiment in Art 1863-1922. Enthused by Gray’s revelation of the way that early Soviet art simply continued a movement that had already gone through a series of “paradigmatic changes”, I wrote a term paper using her book and Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions to explore the issues of continuity and change in “revolutionary episodes”.

This founded my interest in Russian literature and art; and writing this now, some fifty years later, I realise my original interest has not waned in the least. By contrast, my interest in Kuhn did not last the year out. During the summer of 1971 I read more widely in the history and philosophy of science, especially the papers of Paul Feyerabend, the writings of Gaston Bachelard and Georges Canguilhem, and Foucault’s Order of Things. During the early winter of 1971, working in West Berlin, I used this reading to draft a long critique of Kuhn’s ideas about intellectual continuity, the nature of novelty and the forces of innovation. I began postgraduate studies in Cambridge in 1972, and discussed my essay on Kuhn with Paul Hirst; he helped me condense it into an article that was then published in Economy and Society later in 1973.

Tatlin’s Tower is a reminder to me that this concern with the relationship between new and old ideas, and the complexities of change and innovation, came before I had developed a specific interest in the history of politics and economics. Around the same time, taking a course on the History of Sociology in my final year at Essex, I had written an essay on Malthus, stumbling across his Principles of Political Economy (1820) in the university library and thinking that here, in political economy, lay the real sources of the social sciences. My doctoral dissertation on the history of early English political economy did not however take shape until later, written up during 1974-75.

And so, looking back, it now becomes clearer that this concern with the complexities of intellectual change preceded its convergence with, condensation into, a lifelong interest in the circumstances shaping the discipline of economics. As I explain in Constructing Economic Science, the book originated in the later 1980s as a development of ideas shaped by an international project charting the institutionalisation of political economy. But the concern with questions of novelty and innovation – how what might now seem new is merely repetition, that what was once, and still is, new gets forgotten – goes right back to my reading of Camilla Gray in 1971. In her early 20s she had been instrumental in recovering the work of artists, designers, and writers who were persona non grata to the Soviet authorities, and virtually unknown everywhere else. We mostly owe to her our present understanding of the sheer inventiveness of Russian artists, designers, architects, film-makers, engineers and writers during the early decades of the twentieth century. She was only 26 when her seminal study on Russian art was published. By the end of 1971 she was dead, aged 35.

Her book is however still in print. In it she contrasts Tatlin’s beliefs to those of Malevich and Kandinsky, who considered art to be an essential spiritual activity, ordering “man’s vision of the world”.

To organize life practically as an artist-engineer, they claimed, was to descend to the level of a craftsman, and a primitive one at that. … In becoming useful, art ceases to exist. …On the other side, Tatlin and the ardently Communist Rodchenko insisted that the artist must become a technician; that he must learn to use the tools and materials of modern production in order to offer his energies directly for the benefit of the Proletariat. The artist-engineer must build harmony in life itself, transforming work into art, and art into work. ‘Art into life!’ was his slogan, and that of all the future Constructivists – not to be interpreted in the naive and sentimental way in which the ‘Wanderers’ and the Abramtsevo colony had taken ‘art to the people’, by idealizing the peasant and his crafts as the source of life, but by utilizing and welcoming the machine. The machine as the source of power in the modern world would release man from labour, transforming it into art. … The engineer must develop his feeling for materials – through the method of ‘Material culture’ – and the artist must learn to use the tools of mechanical production.

Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art 1863-1922, Thames and Hudson, London 1971 pp. 246-48.